Discover more from Beyond the Rood

To Reconcile All Things to Himself: Beowulf, Homer, and Acculturation of Paganism

"What hath Ingeld to do with Christ?"

“God is the Lord, of angels, and of men and of elves. Legend and History have met and fused. But in God's kingdom the presence of the greatest does not depress the small. Redeemed Man is still man. Story, fantasy, still go on, and should go on. The Evangelium has not abrogated legends; it has hallowed them”

— Tolkien, On Fairy Stories

In many ways, this post will serve as the second part of my earlier essay on Christianity as the Master Narrative which you can find here. Although reading that post is not necessary to understand this one, it may be a helpful way to frame some of the ideas I will be discussing below. While my previous essay was more focused on the philosophical nature of the Christian story as such, consider this essay to be the historical/theological application of those ideas and how they have been understood throughout the Christian tradition.

In the late 8th century, Alcuin of York, an Anglo-Saxon scholar and poet, at the behest of Charlemagne became a scholar of the Carolingian court. In a letter to Higbald of Lindisfarne, an English bishop, Alcuin questioned the monastic interest in pagan literature. Parroting Tertullian’s famous question “What hath Athens to do with Jerusalem?” Alcuin wrote, “Let God's words be read at the episcopal dinner table. It is right that a reader should be heard, not a harpist, patristic discourse, not pagan song. What has Ingeld to do with Christ?”1 He goes on to say “The house is narrow and has no room for both … the Heavenly King does not wish to have communion with pagan and forgotten kings.”

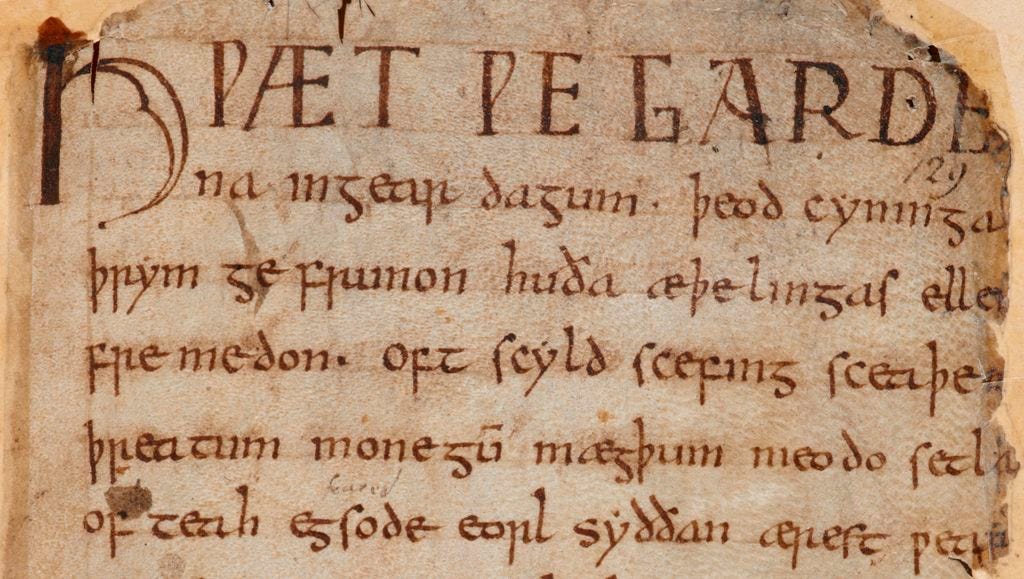

Many who are familiar with Beowulf will know that the poem itself can be read both as an answer to Alcuin’s question as well as a reiteration of it. There are explicitly Christian elements scattered throughout the poem. The Christian influence is so explicit that, although there is almost nothing about Beowulf that is not up for debate, most scholars agree that it was written by a Christian (most likely by a Christian monk) in Anglo-Saxon England sometime between the 8th and 10th centuries.

Readers of Beowulf can often be perplexed as to why a poem that appears to be about a pagan people is constantly referencing “the Lord,” or why the poet frequently mentions that Grendel and his mother are “descendants of Cain” from the Book of Genesis, or why Grendel and his mother are explicitly described as demons throughout.2

After seeing these elements of the poem many are left wondering, like Alcuin, what Ingeld, Grendel, Beowulf, or Hrothgar have to do with Christ. What does Christianity have to do with forgotten pagan kings and gods?

The Virtuous Pagans

Several centuries before the time of Alcuin in the Middle Ages, St Basil the Great in his Address To Young Men On The Right Use of Greek Literature provides a patristic witness to the reception of pre-Christian writing where he, rather shockingly, states that Christian men ought to master Homer before even studying the Holy Scriptures:

“Since the life to come is to be attained through virtue, chief attention must be paid to those passages in which virtue is praised; such may be found, for example, in Hesiod, Homer, Solon, Theognis, and Prodicus […] while this ideal will be matured later by the study of the Scriptures, it is at present to be fostered by the study of the pagan writers; from them should be stored up knowledge for the future.”

Elsewhere in the same letter he writes:

“It is, therefore, in accordance with the whole similitude of the bees, that we should participate in the pagan literature. For these neither approach all flowers equally, not in truth do they attempt to carry off entire those upon which they alight, but taking only so much of them as is suitable for their work, they suffer the rest to go untouched. We ourselves too, if we are wise, having appropriated from this literature what is suitable to us and akin to the truth, will pass over this remainder. And just in plucking the blooms from a rose-bed we avoid the thorns, so also is garnering from such writings whatever is useful, let us guard ourselves against what is harmful.”

St. Basil is not the only one among the early Church Fathers to speak this way about pagan literature. Augustine, Jerome, and Ambrose (who quoted Virgil freely) speak similarly to Basil on the benefits of reading pagan works.

Historically, the early Christians did not see a tension between the pagan elements of ancient literature and their newfound Christianity. On the contrary, they saw them as containing truths that foreshadowed the coming of Christ. This became known by the earliest Christian apologists as the spermatikos logos or the “seeds of truth”, an idea originally coming from the writings of St. Justin Martyr, who believed that although pagan literature was not perfect, it nonetheless contained seeds of true things that were beneficial for Christians.

This provocative quote from Justin highlights how the Christian tradition has historically received pagan writings:

“For I myself, when I discovered the wicked disguise which the evil spirits had thrown around the divine doctrines of the Christians, to turn aside others from joining them, laughed both at those who framed these falsehoods, and at the disguise itself and at popular opinion and I confess that I both boast and with all my strength strive to be found a Christian; not because the teachings of Plato are different from those of Christ, but because they are not in all respects similar, as neither are those of the others, Stoics, and poets, and historians. For each man spoke well in proportion to the share he had of the spermatic word [spermatikos logos; the Logos inherent in all humans], seeing what was related to it. But they who contradict themselves on the more important points appear not to have possessed the heavenly wisdom, and the knowledge which cannot be spoken against. Whatever things were rightly said among all men, are the property of us Christians.”

— St. Justin Martyr, Second Apology, 13

This idea of the virtuous pagan, finding its origin in the writings of St. Justin, is a concept within Christian theology that deals with the question of the fate of those who came before Christ (and therefore had no opportunity to accept Him) but nevertheless led virtuous lives.

In his First Apology, Justin says that those who lived according to reason (logos), although they were atheists3, were still Christians:

“We have been taught that Christ is the first-born of God, and we have declared above that He is the Word of whom every race of men were partakers; and those who lived reasonably are Christians, even though they have been thought atheists; as, among the Greeks, Socrates and Heraclitus, and men like them”

— St. Justin Martyr, First Apology, 46

The Christian philosophers who appropriated Greek philosophy were not condemning the pagans who came before them. On the contrary, they saw them as grasping at the truth that would culminate in Christ. They were the pathfinders of The Way prior to the Incarnation.

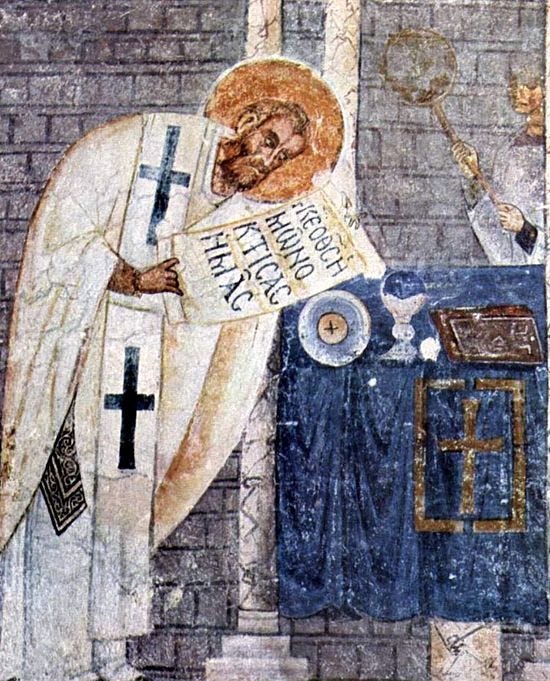

This beautiful icon fresco at the Great Meteoron Monastery in Meteora Greece shows St. Justin Martyr and St. Paul leading the Greek philosophers (who are notably without halos and on the outside the church) to Christ:

In these icons, we see a visual representation of the patristic understanding laid out by St. Basil and St. Justin. The Greek philosophers were primed to accept the teachings of Christ because they had lived in accordance with the share of the truth they had received. What they had begun by the use of natural reason would be elevated and perfected by the theologians and carried to the foot of the cross. Their philosophy, while imperfect, was nonetheless a movement towards the Logos.

We see this especially in the writings of Aristotle and Plato. Aristotle, despite being a pagan, had a decidedly non-pagan metaphysics. He argues in Book XII of his Metaphysics that there must exist an Unmoved mover who is the source of all motion in the universe but who is Himself unmoved.4

Plato, before Aristotle, with frankly astonishing precision, prophesized the death of Christ in The Republic. In discussing justice and injustice, he predicts the coming of a perfectly just man who would die for the sake of the unjust. Through Glaucon, he says:

“Though he do no wrong he must have the repute of the greatest injustice, so that he may be put to the test. ... But let him hold on his course unchangeable even unto death, seeming all his life to be unjust though being just. ... Such being his disposition the just man will have to endure the lash, the rack, chains, the branding iron in his eyes, and finally, after every extremity of suffering, he will be impaled.” — Plato, Republic II, 361c-e

Many would accuse Christianity of appropriating pagan culture for reading the ancient philosophers this way, and in one sense they are right, this is appropriation. However, I reject that this is in any way problematic. If Christ is the Logos, then Christianity is the only story that can coherently make sense of the multiplicity of stories throughout human history and find a way to integrate them into the tradition. Only Christianity is catholic (i.e. universal) enough to take the entire pagan world that came before it and find a way to fit it into a master narrative.

Triumph of Christian Religion

To understand the Christian story properly, one must realize that the Christian God is not a God who came to prove He was the only god who existed, but one who became incarnate to conquer the other gods who did exist. The Old Testament is replete with language that reflects the understanding that the gods of the Gentiles are demons and that the God of Israel casts judgment on them all:

“They sacrificed to demons, not to God, To gods they did not know, To new gods, new arrivals that your fathers did not fear.” — Deuteronomy 32:17

“No, but the sacrifices of pagans are offered to demons, not to God, and I do not want you to be participants with demons.” — 1 Corinthian 10:20

“For all the gods of the Gentiles are demons, but the Lord made the heavens.” — Psalm 96:5

“For the LORD is the great God, the great King above all gods.” — Psalm 95:3

“For I will pass through the land of Egypt that night, and I will strike all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, both man and beast; and on all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments: I am the LORD.” — Exodus 12:12

“God has taken his place in the divine council; in the midst of the gods he holds judgment.” — Psalm 82:1

The gospel, the εὐαγγέλιον (evangelion), is the proclamation of Christ’s triumph over the old gods, that is, over demons, sin, and death. This is why when people accuse Christians of appropriation or ‘theocide’ the only correct response is “yes…that is the point.”

Modern people see the other stories of different gods from other religions and they mistakenly dismiss them as completely arbitrary rather than a particular manifestation of a universal human experience. Once Christianity arrives in history, we see from the teachings of the Fathers that there is a way in which all things culminate into Christ. All the good elements of the ancient traditions that preceded the Incarnation get pulled into the story of Christ, who integrates them into the universal story.

In light of this, we can see works such as the Beowulf poem as an attempt at finding a synthesis between the old pagan world and the new Christian one. It is a microcosm of the Christian story, one that pays respect to the history of the Anglo-Saxons while also recognizing how Christ redeems their story. This kind of acculturation tends to anger certain people who view history and literature through a particular critical lens. In response, I can only repeat what Chesterton says:

“Neo-Pagans have sometimes forgotten; when they set out to do everything that the old pagans did, that the final thing the old pagans did was to get christened.”

It is true that Christ conquers and defeats the old gods, but when those old stories die, they have the capacity to be resurrected and brought in to participate in the story of Christ, who as St. Paul tells us, reconciles all things to Himself.5 This is what Tolkien meant when he said “The Evangelium has not abrogated legends; it has hallowed them.” What is good and virtuous and holy from the old stories is baptized into Christ and invited to participate in His victory. This is what it means to “plunder the Egyptians” as the Book of Exodus says; it is the “plucking the blooms from a rose-bed to avoid the thorns” to repeat St. Basil’s phrase in his letter above. It is recognition that all truth, all goodness, and all beauty belong to Christ who makes all things new.6

So, to answer Alcuin…what has Ingeld to do with Christ?

The answer can be summarized in one succinct story from Andrew Louth’s book Greek East and Latin West: The Church AD 681-1071:

…Among the writings ascribed to the seventh-century abbot of Sinai, Anastasios, there is a story which relates that it was the custom of a certain learned Christian to curse Plato daily, until eventually Plato himself appeared to him and said, "Man, stop cursing me; for you are merely harming yourself. I do not deny that I was a sinner, but, when Christ descended into hell, no one believed in Him sooner than I did."

For those not familiar with the Beowulf poem, Ingeld is the son of Kind Froda of the Heaðobards, who are at war with the Danes.

To read a fascinating scholarly article on the connection between the Beowulf poem and the Old Testament Apocrypha, see this article “Beowulf and the Book of Enoch” by R.E. Kaske.

Note that by “atheist” Justin does not mean the modern notion of atheism (i.e. someone who doesn’t believe any gods exist) but rather he means someone who doesn’t worship the Christian God. In the early Church, Christians were accused of atheism by the Romans because they did not offer sacrifices to the Roman gods, something Justin discusses at length in the First Apology.

“The first principle and primary reality is immovable, both essentially and accidentally, but it excites the primary form of motion, which is one and eternal. Now since that which is moved must be moved by something, and the prime mover must be essentially immovable, and eternal motion must be excited by something eternal, and one motion by some one thing; and since we can see that besides the simple spatial motion of the universe (which we hold to be excited by the primary immovable substance) there are other spatial motions—those of the planets—which are eternal (because a body which moves in a circle is eternal and is never at rest—this has been proved in our physical treatises; then each of these spatial motions must also be excited by a substance which is essentially immovable and eternal. For the nature of the heavenly bodies is eternal, being a kind of substance; and that which moves is eternal and prior to the moved; and that which is prior to a substance must be a substance. It is therefore clear that there must be an equal number of substances, in nature eternal, essentially immovable, and without magnitude; for the reason already stated […] It is evident that there is only one heaven. For if there is to be a plurality of heavens (as there is of men), the principle of each must be one in kind but many in number.But all things which are many in number have matter (for one and the same definition applies to many individuals, e.g. that of "man"; but Socrates is one , but the primary essence has no matter, because it is complete reality. Therefore the prime mover, which is immovable, is one both in formula and in number; and therefore so also is that which is eternally and continuously in motion. Therefore there is only one heaven.”

— Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book XII, 1073a-1074b

Colossians 1:19–20

Revelation 21:5

Subscribe to Beyond the Rood

A look into the mysteries behind the veil.

Thank you for this. Aligns with J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis' description of the gospel and of Christ as "myth made fact."

This is excellent.