Discover more from Beyond the Rood

Christianity as the Master Narrative: Tolkien, Lewis & the Phenomenology of History

Myth made fact

“Do we walk in legends or on the green earth in the daylight?'

A man may do both,' said Aragorn. 'For not we but those who come after will make the legends of our time. The green earth, say you? That is a mighty matter of legend, though you tread it under the light of day!”― J.R.R. Tolkien, The Two Towers

I recently appeared on an episode of the I Might Believe In Fairies podcast where we discussed a variety of topics including phenomenology, the mythological structure of the liturgy, and Tolkien and Lewis’ view of myth and storytelling based on Lewis’ essay “Myth Became Fact.”

I had such a good time speaking with Aaron that the conversation inspired me to collect some of the thoughts I had prepared prior to our discussion into a more formal write-up as well as write about a few things we didn’t get the chance to cover.

Modern people tend to create a false dichotomy between history and myth. The colloquial understanding is that history is what is true, based on facts and evidence, while myths are false, made-up stories that perhaps have some allegorical application but are nonetheless “lies breathed through silver” as C.S. Lewis famously said before his conversion. Upon closer examination, however, we discover that history itself is not as objective or empirical as certain 19th-century historians would like us to believe.

The unavoidable truth is that history is a narrative.

“History often resembles ‘Myth’, because they are both ultimately of the same stuff.” — J.R.R Tolkien, On Fairy Stories

Any retelling of a historical event can never be done with pure factuality. History does not record facts, it records a story about what is meaningful to us. There are an infinite amount of facts that could be recorded about any given historical event, things like what Abraham Lincoln ate for breakfast the morning he was assassinated or how many times George Washington blinked while crossing the Delaware River. When someone asks about your day they aren’t interested in hearing exactly how many breaths you took or the number of times you blinked because, while these things are measurable data, they are meaningless. They are not relevant to our experience or of interest to anyone.

Reality consists of too many details. It is too big to focus our attention on everything even though the most minute detail is part of what really happened (at least according to the materialist). Any description of an event must focus attention on certain aspects while ignoring others. It requires a purpose to frame it. There is no such thing as a purely neutral recollection or description of an event that is not already imbibed with meaning and purpose. Any description of an event requires attention to be focused on certain facts that are relevant to the story while others are ignored because they are not relevant to the story. We understand history through narrative, through myth, because as Tolkien said, they are both made of the same stuff. History is not a matter of fact, it is a matter of myth.

For many, alarm bells may be going off because I said something that sounds vaguely postmodern. If I may digress for a moment to say two things: First, the problem with postmodernism is not the view of history in terms of narrative per se but rather, the view of history in terms of many competing narratives all understood as social constructions centered around a desire for maintaining power structures. This is (obviously?) not the understanding I will attempt to put forth, which is about how myth and storytelling play a vital role in our perception of the world, our understanding of ourselves and our history, and ultimately our place in the master narrative of the cosmos (anyone who knows anything about postmodernism knows it rejects the idea of meta-narrative outright).

The second thing I would say is that even if there is an overlap between what certain phenomenological approaches and postmodernism have to say about reality, this is not in itself a bad thing. We should not be low-resolution thinkers. Postmodernism is certainly a garbage heap of horrible and dangerous ideas, but it is not wrong about everything. I have found it helpful to understand postmodernism as an overreaction to Enlightenment Rationalism and one of the few good things the postmoderns got right was a return to understanding ourselves as being part of the story again (contra modernism which tends to view the world through a lens of hyper-objectivity as if we do not exist in it). This turn towards the subject and viewing ourselves as being part of the narrative is very much a pre-modern way of thinking which is fitting for discussing the thought of medievalists such as Tolkien and Lewis.

Having attempted to preempt the critique, let’s return to the point at hand…

The pervasive modernist idea that we somehow have access to an unmediated, purely objective, and totally neutral description of something is seen most clearly when people debate whether or not the descriptions founds in the Bible are ‘literal’. When people treat the stories in the Scriptures like they are a forensic description of an event, they try to get behind the story to uncover what ‘really happened’ and lose any deeper meaning in the text. What most people mean by ‘really happened’ is something akin to if we somehow were able to go back in time and take a photograph of the event or record a video of it, it would perfectly match the written account.

The problem that so many Christians have is that they, even unknowingly, have adopted the modern materialist/empiricist presuppositions that scientific knowledge is the highest form of knowing, and so they become fixated on justifying their religious beliefs according to those axioms. By obsessing over things like trying to prove certain Biblical events really took place using archaeological evidence or trying to show the earth really is only about 6000 years old, many modern Christians become functionally materialists.

This is essentially just losing at a game Christianity doesn’t need to play. Asking whether the earth is 6000 years old or 6 billion years old is a meaningless question, and I don’t say that to be provocative. It is the same as asking the age-old question; if a tree falls in the forest and no one is around does it make a noise? Our collective human memory, the stories, and myths we have maintained, only go back about 7500 years. There is nothing prior to that that is part of our memory, our culture, our traditions, our conscious experience, or our connection to the past. It is not part of our story. 6 billion years that we have no memory or experience of is a meaningless amount of time, it might as well be an instant.

This phenomenological view of history can be destabilizing for some, but it highlights how foolish it is to try and use the scientific method to prove the events of the Bible are true, despite the fact that the story of Genesis is not at all concerned with describing how old the Earth is or giving us a materialistic description of the Fall of Man. We cannot interpret ancient stories with modern categories. Approaching the Bible this way is tantamount to refusing to read Shakespeare because the events depicted are fiction, and in doing so would lose the forest for the trees. It is a category error based on entirely faulty epistemic principles and a misunderstanding of the kind of book(s) the Scriptures are.

Perception as Narrative

The role that our conscious experience in our view of the world is not only vital to understanding how we explain the past, but it also plays a fundamental role in our perception of reality altogether.

We have gone through a moment in history where scientific materialism has dominated the cultural zeitgeist. This way of thinking is quickly approaching its breaking point, however. Physicists are starting to realize that once you reduce everything down to its materials, once you understand everything in terms of its mechanical causality and physical parts, there is still a lot about reality that is left unaccounted for. Things such as consciousness, human experience, love, identities, qualities, etc. are found to be unexplainable and so the materialist is left trying to deal with things like the Hard Problem of Consciousness that highlight the impossibility of trying to explain all of reality using only the material world. They try to save face by coming up with words like “emergence” (which is really just a fancy word for ‘magic’ although they will never admit it) to try and explain what their system cannot account for, but ultimately this tactic is just placing a name where a theory ought to be, and still leaves these phenomena unaccounted for.

Even trying to understand how things exist in both unity and multiplicity becomes an unsolvable puzzle for materialism. To use a cliche example, how is it that we can say a chair is one thing and yet also recognize it as a multiplicity of things? When we see a chair we see a single object, however we also know that it is composed of parts. Why don’t we just see those parts rather than a unified whole? Furthermore, why don’t we just see the parts that make up each of the parts? After all, every part of the chair (the wood, the screws, the paint, etc.) is also made up of other parts. Why is it that we do not see the multiplicity all the way down to the atomic structure or even some nebulous quantum flux?

What we have come to discover, especially with the rise of quantum physics, is that once you get to the bottom of materialism, the world becomes narrative again. Our consciousness plays a role in the unfolding of reality. Even something as simple as a chair cannot have an identity from its material constitution. Things gather and cohere into unity at different levels of reality in human experience. Our perceptions are part of the story. This is true of our experience of the environment around us just as much as it is true of our understanding of our histories.

We cannot try and view the world as if we do not exist in it. There is no view from nowhere and the world presents itself to us in a storied manner, a story that we are necessarily a part of.

Man does not experience reality in a scientific way. When we perceive the world we do not see facts, we see meaning and narrative. When I encounter a tree I do not see its molecular structure or its biological makeup. Rather, I see something beautiful, good for shade, a thing I can climb or sit under and read a book, something that makes a certain noise when it is blown in the wind. When I drink a glass of water I am not drinking or experiencing H2O, I drink cold, refreshing, wet, clear, etc.

Tolkien understood this very clearly. In his poem Mythopoeia that he wrote in response to C.S. Lewis, Tolkien writes:

There is no firmament,

only a void, unless a jewelled tent

myth-woven and elf-patterned; and no earth,

unless the mother’s womb whence all have birth.

The heart of Man is not compound of lies,

but draws some wisdom from the only Wise,

and still recalls him.

What Tolkien is presenting in this stanza of the poem is the necessity of narrative in our perception of the world. Unless our frame is “myth-woven and elf-patterned” there is no firmament, no earth. The heart of man, which experiences the world in a narrative fashion, is not lying to us, but rather, is drawing this wisdom from the only Wise, God.

Likewise in his essay On Fairy Stories, Tolkien emphasizes how our initial perceptions of the world and the language we use to describe them are all part of a story:

“The incarnate mind, the tongue, and the tale are in our world coeval. The human mind, endowed with the powers of generalization and abstraction, sees not only green-grass, discriminating it from other things (and finding it fair to look upon), but sees that it is green as well as being grass.

But how powerful, how stimulating to the very faculty that produced it, was the invention of the adjective: no spell or incantation in Faerie is more potent. And that is not surprising: such incantations might indeed be said to be only another view of adjectives, a part of speech in a mythical grammar. The mind that thought of light, heavy, grey, yellow, still, swift, also conceived of magic that would make heavy things light and able to fly, turn grey lead into yellow gold, and the still rock into a swift water.”

Of course, for modern people, this phenomenological way of viewing the world can be a bit nebulous and it is often discarded for a more disenchanted utilitarian understanding. Rather than seeing a forest for the mysterious, dangerous, and enchanted place it is, we see a deposit of resources that can be torn down, chopped up, and used as fuel for some kind of machine. Even our basic perceptions of the world are supplemented by technology. For many, what can be seen under a microscope or through a telescope is somehow more real than what is seen with the naked eye.

That is the great paradox of modern Man, to view that which is made artificially as if it were someone more real or meaningful than our natural human experience of reality. We have somehow convinced ourselves that looking at the world through machines is someone more real than what our own eyes perceive. We have adopted a “mind of metal and wheels” to quote Treebeard’s description of Saruman. Not only is this way of viewing the world artificial, but it is also alienating in that it moves Man away from himself and his own experience towards a disembodied mode of being.

This is what we might call propositional vs. participatory knowing. The scientific mind looks at something like a tree and proposes that to truly understand it and to know true things about it we must cut it down, dissect it, and analyze it under a microscope by breaking it down into small quantitative parts that can be measured and calculated. However, those who live in the enchanted world know that the only way to understand trees is to live in communion with them and experience them directly.

When a man is said to love his wife this is not a statement that can be proven by some kind of logical formula following premises to a conclusion. Love cannot be looked at under a microscope or created in a lab. Love must be experienced! Spouses share an intimate knowledge of one another that could never be explained in a book. Their experience of being in relation to one another can barely be described using words let alone formulae. There is no machine that can measure it quantitatively. Contrary to the philosophical assumptions of the so-called Enlightenment, rationalism is an utterly insufficient epistemology. Some things can never be known by mere logic alone, but can only be revealed by our direct experience of them and how they fit into our story.

“The cosmos is not a kind of closed building, a stationary container in which history may by chance take place. It is itself movement, from its one beginning to its one end. In a sense, creation is history.” — Joseph Ratzinger

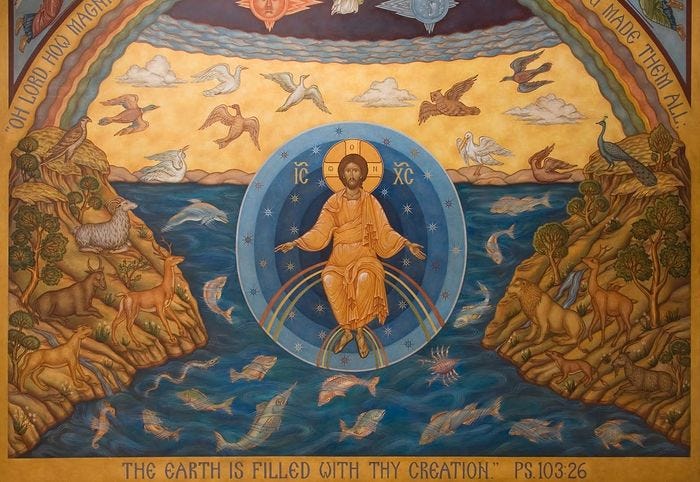

Just like history is not a collection of meaningless facts, neither is our perception of the world. Reality unveils itself to us as “myth-woven”. The cosmos is not an empty container where events unfold, but rather, it is itself the frame, it is part of the story. The created world comes from God and is returning to Him. This is the story we find ourselves in. This is the master narrative, it is the Universal Story that culminates in the Incarnation of the Logos, who is Himself the Master Pattern. This is the Christian way of explaining reality. The world is made by Logos — by meaning and purpose. The Christian world is one of the union of heaven and earth where the whole cosmos acts as a sort of sacrament, pointing to its origin and moving towards its final end of deification.

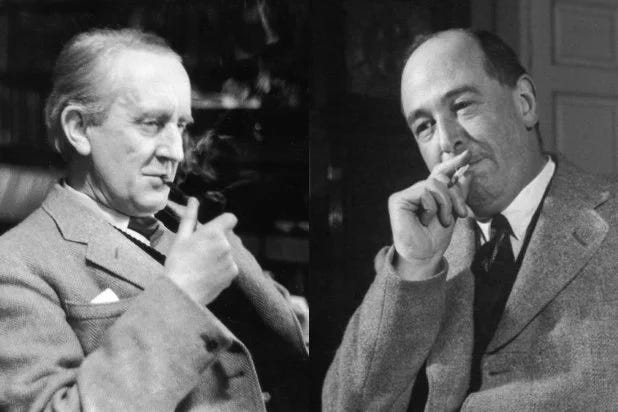

Myth Made Fact

C.S. Lewis’ conversion was due, in large part, to Tolkien’s own understanding of myth and the influence it had on Lewis as a young Oxford Don. There is a famous conversation that Tolkien and Lewis had one evening while walking the grounds of Oxford on Addison’s Walk that proved to be fundamental in the development of Lewis’ thoughts on myth.

In Humphrey Carpenter’s J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography he recounts a version of this conversation:

“But,” said Lewis, “myths are lies, even though lies breathed through silver.”

”No,” said Tolkien, “they are not.”“You call a tree a tree,” he said, “and you think nothing more of the word. But it was not a 'tree' until someone gave it that name. You call a star a star, and say it is just a ball of matter moving on a mathematical course. But that is merely how you see it. By so naming things and describing them you are only inventing your own terms about them. And just as speech is invention about objects and ideas, so myth is invention about truth.”

”We have come from God” (continued Tolkien), “and inevitably the myths woven by us, though they contain error, will also reflect a splintered fragment of the true light, the eternal truth that is with God. Indeed only by myth-making, only by becoming a 'sub-creator' and inventing stories, can Man aspire to the state of perfection that he knew before the Fall. Our myths may be misguided, but they steer however shakily towards the true harbour, while materialistic 'progress' leads only to a yawning abyss and the Iron Crown of the power of evil.”

”You mean,” asked Lewis, “that the story of Christ is simply a true myth, a myth that works on us in the same way as the others, but a myth that really happened? In that case, he said, I begin to understand.”

This conversation (and others) with Tolkien left a lasting mark on Lewis’ life and was paramount in his conversion to theism and eventually to Christianity proper. Lewis’ later writings on myth and storytelling are clearly influenced heavily by Tolkien’s own philosophy of storytelling. Lewis writes in his essay Myth Became Fact:

“What flows into you from the myth is not truth but reality (truth is always about something, but reality is that about which truth is), and, therefore, every myth becomes the father of innumerable truths on the abstract level. Myth is the mountain whence all the different streams arise which become truths down here in the valley…Now as myth transcends thought, incarnation transcends myth. The heart of Christianity is a myth which is also a fact. The old myth of the dying god, without ceasing to be myth, comes down from the heaven of legend and imagination to the earth of history. It happens-‐at a particular date, in aparticular place, followed by definable historical consequences. We pass from a Balder or an Osiris, dying nobody knows when or where, to a historical person crucified (it is all in order) under Pontius Pilate. By becoming fact it does not cease to be myth: that is the miracle.”

This passage from Lewis is not only deeply cohesive with his and Tolkien’s Oxford conversation but also with Tolkien’s Epilogue in On Fairy Stories:

“The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. They contain many marvels - peculiarly artistic,' beautiful, and moving: 'mythical' in their perfect, self-contained significance; and among the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe. But this story has entered History and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation. The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man's history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation.”

For both Tolkien and Lewis, the significance of the Christian story cannot be overstated. In the Incarnation, the narrative world and the objective world meet and become one. In Christ, myth is made fact. Heaven and Earth touch. The spiritual world is married to the material world. Contained within the story of the Incarnation is the essence of all myths, all fairy-stories. Christ as the Master Pattern, the Logos, gathers all things, all stories, all myths, into Himself. The story of Christ contains and perfects all other stories and in so doing, allows us to echo the words of St. Justin Martyr “whatever true things have been said amongst all men, is the property of us Christians.” In this way, Christianity truly is the master narrative, the narrative that accounts for all of reality and has the ability to integrate all stories into the universal one.

Liturgy — Living in the Story of Christ

Earlier I mentioned the difference between propositional vs. participatory knowing and this distinction is why the sacraments of the church are so important. They are called the Sacred Mysteries because they can never be fully grasped by reason alone. They are nonetheless a form of divine pedagogy as they are God’s way of communicating Himself to us through our direct experience of Him and His Energies/Activity.

These mysteries are how we ritually participate in the story of Christ in a way that goes far beyond the reductionistic view that approaches the Gospels as a literary critic. The Christian myth is not a dead story that is merely consumed or analyzed, it is something we are meant to enter into. We are not gnostics. We have to embody the faith through praxis. For the true Christian, the faith is not simply a list of assertions and propositions abstracted out of a text that we assent to intellectually, it is an embodied (enfleshed, incarnated) way of life.

Stories are not things we consume and analyze to abstract meaning out of. That is a modern way of looking at the world. In modernity, stories have become commodified pieces of entertainment used as a vehicle for an emotional high. Ancient stories and myths, the ones passed on and remembered for thousands of years, were not a product to be purchased but were part of the mythos that define us and who we are, why we are here, and where we are going. They also supersede any literary form. They are living stories. As such, these stories are meant to be kept alive through our ritual participation in them. We are part of the cosmic story that is reality and we are called to participate in that reality, not observe it from the outside as if we were not part of the narrative.

Those who experience the liturgical life of the Church know the beauty of watching the story of Christ unfold over the course of the liturgical year, culminating, as it just did, in the feast of the Resurrection. This narrative view of the world is fulfilled most perfectly through sacrament, through the divinization of the cosmos by the elevation of the lowest things by participation in the highest things. It has been said that the Gospel is a song that takes the Church an entire year to sing and there is immense truth in that. Participating in the liturgical life of the church is like living in an epic poem that permeates every aspect of our lives.

Without liturgy, Christianity is flat. The story of Christ is not one that should be consumed but is one that should consume us. The disenchantment of the world comes along with the commodification of stories, and the commodification of stories follows from the denial of sacrament. It is not a coincidence that the Reformation was preceded by debates about the nature of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, nor was it a coincidence that the Enlightenment followed the outright denial of the sacrament. A rejection of a sacramental world is what led to the secularization of the West.

“We can regard Christian fantasy-writing as the outcome of an imagination that works in sacramental terms, seeing the material world as participant in, and mediator of, the divine” - Heather Ward, Earth’s Crammed with Heave: Fantasy and Sacramnetal Imagination in George MacDonald

This push to “demythologize” Christianity, to rid it of all its “superstition”, has led to what is essentially a gnostic version of the faith. For many Christians (particularly in the United States) Christianity is simply a matter of belief, of intellectually assenting to certain propositions in order to be “saved”. The problem with this understanding is that true belief must be embodied in praxis, as St. Maximos the Confessor said “Theology without practice is the theology of demons”. The Christian faith is not a matter of the mind but of the whole person.

As much as I have appreciated much of the work of Jordan Peterson over the years, I think it is quite dangerous to approach the biblical stories simply as cautionary tales or self-help parables. It’s not enough to understand these stories psychologically. They have to be lived in. To “act as if God exists” (as Peterson is so fond of saying) is to participate in the story of Christ through the worship of the One, Holy, and Undivided Trinity.

“God is the lord of angels, and of men, and of elves. Legend and History have met and fused.” - J.R.R. Tolkien, On Fairy Stories

As Christians, we need not be afraid of understanding our own myths as myths! After all, as Tolkien said, God is not only the lord of angels and men but also of elves. Through the Incarnation, the objective world and the narrative world meet. The mighty world of legend enters into our history and the realm of human experience. It is only by learning to hear the Music of the Ainur and see the Deep Magic that we can hope to recover the enchanted world and the sacramental imagination.

In this essay I touched on a variety of different topics and sources pulling from multiple works from both Lewis and Tolkien and so I thought it would be a good idea to provide a short reading list for anyone who wants a more complete exposure to their thought on myth and storytelling. This essay has, hopefully, but scratched the surface of their thought and I, of course, could never exhaust their brilliance in a single essay. This list is by no means complete but it is more than enough for a well-rounded study of their material:

J.R.R. Tolkien:

"On Fairy-Stories"

"Mythopoeia"

C.S. Lewis:

"On Stories" (in Of Other Worlds)

"On Criticism" (in Of Other Worlds)

"On Myth" (Chapter 5 of Experiment in Criticism)

"The Meanings of 'Fantasy'" (Chapter 6 of Experiment in Criticism)

The Discarded Image

Subscribe to Beyond the Rood

A look into the mysteries behind the veil.

This is a wonderful article with insights well stated, especially the validation of parts of postmodern thought. But the article, along with many others of the same content, eclipses the one Inkling, namely Barfield, who was really the leading figure when it came to themes of participatory knowledge and the "rediscovery of meaning." While his fiction never put him on the same standing as Lewis and Tolkien, it does seem like Barfield deserves wider attention for his groundbreaking ideas in his philosophical works. At least one reason for this redressment is to acknowledge the ways in which Barfield both directly and indirectly fed the imaginations and intellects of Lewis and Tolkien.

Beautiful explained. Majority of Christians in the West are materialists. Since I’ve started to unpick my materialistic world view and begun to return to an ancient mindset, I feel so much more connected to God, the Bible and Creation.